Julius Caesar Overview

From Shmoop Website on Julius Caesar (also a GREAT vid on Ethos, Pathos, Logos)

What is Julius Caesar About and Why Should I Care?

Betrayal. Brutus places his ideals (Rome as a republic) over his friend, Julius Caesar, and is willing to kill Caesar to protect the Republic.

Fear. Incredibly afraid of losing Rome as a republic, Brutus is willing to murder Caesar before the guy even does anything wrong. In his mind, it's better to sacrifice an innocent ruler than risk his becoming a tyrant.

Political Turmoil. Things don't go according to plan. The politicians are like, "the citizens are going to kiss our togas for eliminating the tyrant Caesar! Down with absolute power." But the citizens are like, "What! You killed Caesar? We loved him." Let's just say that the politicians aren't exactly tuned in to the citizens' wants and needs.

Reason vs. Passion. With his clear, cool logic, Brutus convinces the concerned public that Caesar was a tyrant who needed to be eliminated in order for them to be free. Then along comes Antony, with his passionate, emotional appeal, who just as easily swings the public in the other direction, turning them into an angry mob determined to avenge their beloved Caesar.

Sacrificing Personal Morals for the "Greater Good." Brutus is well-known for being a moral and honest guy, yet he decides to commit murder and sacrifice his morals in hopes of ensuring a better future for Rome

Characters

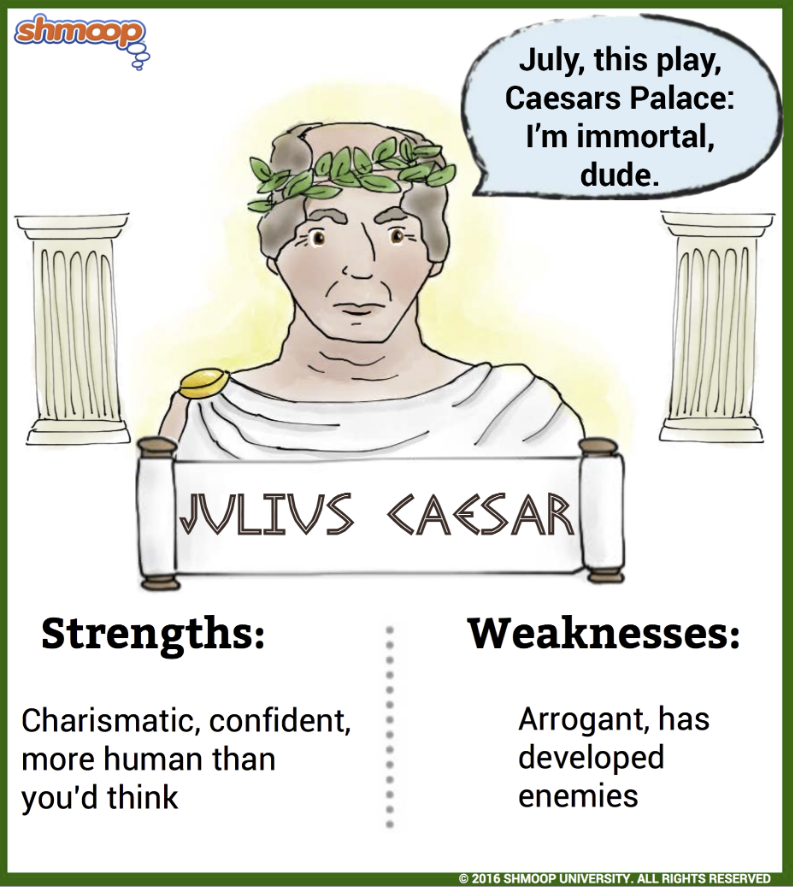

Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar is a powerful Roman political and military leader who gets stabbed in the back (and the arms, legs, and guts!) by a group of conspirators who are supposed to be his friends.

Caesar the Drama Queen

The one thing we do know for sure about Caesar is that he is a total drama queen who likes to put on a big show. When he returns to Rome at the beginning of the play, he parades through the streets like he's a rock star (1.1). (Does this remind you of any modern-day politicians?) The clearest example of Caesar's theatricality is when he appears before the crowd during the Feast of the Lupercal. After refusing the crown Antony offers him, he faints dramatically and then apologizes for his behavior (1.2). The crowd eats it up, of course. As Casca points out, when Caesar acts this way the crowd "clap[s]" and "hiss[es]" for him like he's an actor "in the theater" (1.2).

Caesar the Ambitious Tyrant?

We hear a lot about Caesar from the conspirators, who want to take him down before he becomes even more powerful than he already is. Because Caesar is so popular with the commoners, the conspirators worry he'll be crowned king, turning the republican (in the sense of democratic) government into a monarchy.

He would be crowned:

How that might change his nature, there's the

question.

It is the bright day that brings forth the adder,

[...]

And therefore think him as a serpent's egg

Which, hatched, would, as his kind, grow

mischievous,

And kill him in the shell. (2.1.12-15; 33-36)

Here Brutus compares Caesar to a "serpent's egg" that should be eliminated before it hatches and becomes dangerous. This suggests that the conspirators see in Caesar a future threat to Rome. They're afraid of Caesar not because he is a tyrant, but because he might become a tyrant if he gains more power by being crowned king.

On the other hand, there may be some evidence that Caesar is already beginning to show signs of tyranny. When Casca says that Murellus and Flavius have been "put to silence" for covering up pictures of Caesar during the Feast of Lupercal, we're left to wonder if Caesar has them put to death:

[...] I could tell you more

news too: Marullus and Flavius, for pulling scarves

off Caesar's images, are put to silence. Fare you

well. There was more foolery yet, if I could remember

it. (1.2.295-299)

Caesar the Non-Threat?

Still, for a guy who is supposed to be a major threat to Rome, Caesar sure does have a lot of physical ailments and handicaps, don't you think? Early on in the play we learn that his hearing is impaired (in 1.2.13 he makes Antony stand on his right side because his left ear is "deaf"). We're also told by Cassius that Caesar is a lousy swimmer (he almost drowned once) and that he became very sick as a young man (1.2). Later, in Act 1, Scene 3, we hear that he suffers from something resembling epileptic fits. Shakespeare also raises the possibility that Caesar may have been impotent or sterile: when Caesar announces that Calphurnia is "barren," it's clear the couple is childless, but we wonder if Caesar is the one with the problem.

So why does Shakespeare go to so much trouble to show us how imperfect Caesar is when he's supposed to be such a major threat to the Roman Republic? Shakespeare may just be showing us that Caesar is as human as the rest of us. But might he also be suggesting that Caesar isn't as big a threat as the conspirators make him out to be? Or do Caesar's multiple physical problems suggest that he's not fit to rule Rome? What do you think?

Julius Caesar Superstar?

We've just seen how the play goes out of its way to show us that Julius Caesar is no superhero, but that doesn't prevent Caesar from seeing himself as the biggest "star" in the galaxy. Check out this famous speech, in which arrogant Caesar compares himself to the Northern Star:

I could be well moved, if I were as you.

If I could pray to move, prayers would move me.

But I am constant as the northern star,

Of whose true fixed and resting quality

There is no fellow in the firmament.

The skies are painted with unnumbered sparks;

They are all fire and every one doth shine.

But there's but one in all doth hold his place.

So in the world, 'tis furnish'd well with men,

And men are flesh and blood, and apprehensive.

Yet in the number I do know but one

That unassailable holds on his rank,

Unshaked of motion; and that I am he

Let me a little show it, even in this:

That I was constant Cimber should be banished

And constant do remain to keep him so. (3.1.64-79)

During this famous "I'm the brightest star in the sky" speech, Caesar claims to be the most "constant" (steady) guy in the universe because he can't be swayed by the personal appeals of other men. This says a lot about Caesar's character, don't you think? When Caesar aligns himself with the "northern star," he attempts to elevate himself above all other men. According to Caesar, even though there are other stars (men) in the sky (Rome), "there's but one in all doth hold his place." In other words, Caesar claims that he's the only guy solid enough to rule Rome (as evidenced by his refusal to relent after having banished Cimber).

The irony here is that Caesar delivers this big, fancy speech mere seconds before he's assassinated. Just as our superstar declares how "unshak[able]" and immovable he is, the conspirators surround him and stab him to death (33 times!), unseating him from power. But before we conclude that Julius Caesar isn't as "constant" as he claims to be, let's not forget that centuries after the historical (and still famous) Caesar was assassinated, Shakespeare wrote a play about him...and we're still reading it.

Caesar the Drama Queen

The one thing we do know for sure about Caesar is that he is a total drama queen who likes to put on a big show. When he returns to Rome at the beginning of the play, he parades through the streets like he's a rock star (1.1). (Does this remind you of any modern-day politicians?) The clearest example of Caesar's theatricality is when he appears before the crowd during the Feast of the Lupercal. After refusing the crown Antony offers him, he faints dramatically and then apologizes for his behavior (1.2). The crowd eats it up, of course. As Casca points out, when Caesar acts this way the crowd "clap[s]" and "hiss[es]" for him like he's an actor "in the theater" (1.2).

Caesar the Ambitious Tyrant?

We hear a lot about Caesar from the conspirators, who want to take him down before he becomes even more powerful than he already is. Because Caesar is so popular with the commoners, the conspirators worry he'll be crowned king, turning the republican (in the sense of democratic) government into a monarchy.

He would be crowned:

How that might change his nature, there's the

question.

It is the bright day that brings forth the adder,

[...]

And therefore think him as a serpent's egg

Which, hatched, would, as his kind, grow

mischievous,

And kill him in the shell. (2.1.12-15; 33-36)

Here Brutus compares Caesar to a "serpent's egg" that should be eliminated before it hatches and becomes dangerous. This suggests that the conspirators see in Caesar a future threat to Rome. They're afraid of Caesar not because he is a tyrant, but because he might become a tyrant if he gains more power by being crowned king.

On the other hand, there may be some evidence that Caesar is already beginning to show signs of tyranny. When Casca says that Murellus and Flavius have been "put to silence" for covering up pictures of Caesar during the Feast of Lupercal, we're left to wonder if Caesar has them put to death:

[...] I could tell you more

news too: Marullus and Flavius, for pulling scarves

off Caesar's images, are put to silence. Fare you

well. There was more foolery yet, if I could remember

it. (1.2.295-299)

Caesar the Non-Threat?

Still, for a guy who is supposed to be a major threat to Rome, Caesar sure does have a lot of physical ailments and handicaps, don't you think? Early on in the play we learn that his hearing is impaired (in 1.2.13 he makes Antony stand on his right side because his left ear is "deaf"). We're also told by Cassius that Caesar is a lousy swimmer (he almost drowned once) and that he became very sick as a young man (1.2). Later, in Act 1, Scene 3, we hear that he suffers from something resembling epileptic fits. Shakespeare also raises the possibility that Caesar may have been impotent or sterile: when Caesar announces that Calphurnia is "barren," it's clear the couple is childless, but we wonder if Caesar is the one with the problem.

So why does Shakespeare go to so much trouble to show us how imperfect Caesar is when he's supposed to be such a major threat to the Roman Republic? Shakespeare may just be showing us that Caesar is as human as the rest of us. But might he also be suggesting that Caesar isn't as big a threat as the conspirators make him out to be? Or do Caesar's multiple physical problems suggest that he's not fit to rule Rome? What do you think?

Julius Caesar Superstar?

We've just seen how the play goes out of its way to show us that Julius Caesar is no superhero, but that doesn't prevent Caesar from seeing himself as the biggest "star" in the galaxy. Check out this famous speech, in which arrogant Caesar compares himself to the Northern Star:

I could be well moved, if I were as you.

If I could pray to move, prayers would move me.

But I am constant as the northern star,

Of whose true fixed and resting quality

There is no fellow in the firmament.

The skies are painted with unnumbered sparks;

They are all fire and every one doth shine.

But there's but one in all doth hold his place.

So in the world, 'tis furnish'd well with men,

And men are flesh and blood, and apprehensive.

Yet in the number I do know but one

That unassailable holds on his rank,

Unshaked of motion; and that I am he

Let me a little show it, even in this:

That I was constant Cimber should be banished

And constant do remain to keep him so. (3.1.64-79)

During this famous "I'm the brightest star in the sky" speech, Caesar claims to be the most "constant" (steady) guy in the universe because he can't be swayed by the personal appeals of other men. This says a lot about Caesar's character, don't you think? When Caesar aligns himself with the "northern star," he attempts to elevate himself above all other men. According to Caesar, even though there are other stars (men) in the sky (Rome), "there's but one in all doth hold his place." In other words, Caesar claims that he's the only guy solid enough to rule Rome (as evidenced by his refusal to relent after having banished Cimber).

The irony here is that Caesar delivers this big, fancy speech mere seconds before he's assassinated. Just as our superstar declares how "unshak[able]" and immovable he is, the conspirators surround him and stab him to death (33 times!), unseating him from power. But before we conclude that Julius Caesar isn't as "constant" as he claims to be, let's not forget that centuries after the historical (and still famous) Caesar was assassinated, Shakespeare wrote a play about him...and we're still reading it.

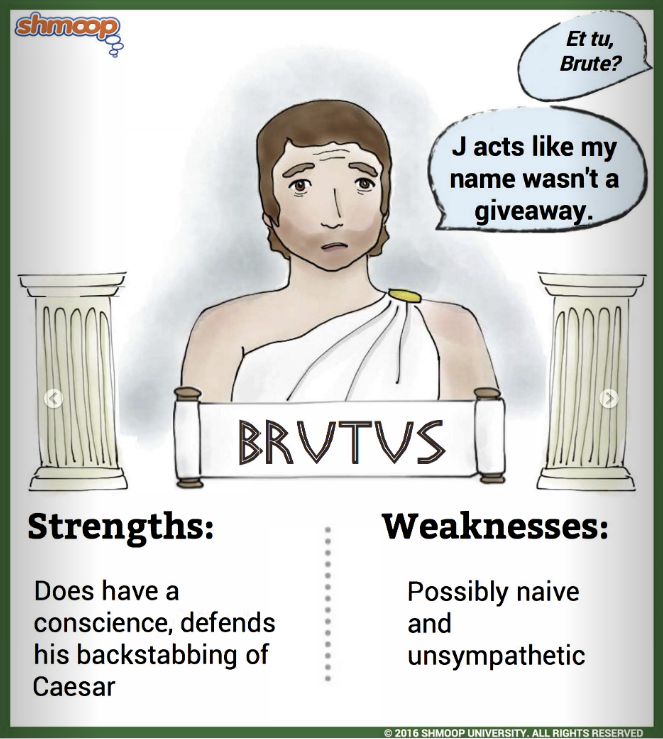

Brutus

One of the conspirators, Brutus is supposed to be Julius Caesar's BFF but he ends up stabbing his so-called pal in the back, literally and figuratively. Does this make Brutus a villain worthy of a Lemony Snicket novel? Not necessarily, but we'll let you decide.

Biggest Backstabber Ever or Roman Hero?

Brutus' decision to stab Caesar in the back isn't an easy one. He has to choose between his loyalty to the Roman Republic and his loyalty to his friend, who seems like he could be heading toward tyrant status. When Brutus hears how the commoners are treating Caesar like a rock star, he's worried for Rome:

BRUTUS

What means this shouting? I do fear the people

Choose Caesar for their king.

CASSIUS

Ay, do you fear it?

Then must I think you would not have it so.

BRUTUS

I would not, Cassius, yet I love him well. (1.2.75-89)

Even though Brutus "love[s]" Caesar "well," he also fears that his friend will be crowned king, which goes against the ideals of the Roman Republic.

After killing his pal and washing his hands in his blood, Brutus defends his actions:

If there be any in this assembly, any dear

friend of Caesar's, to him I say that Brutus' love

to Caesar was no less than his. If then that friend

demand why Brutus rose against Caesar, this is my

answer: not that I loved Caesar less, but that I loved

Rome more. (3.2.19-24)

OK, fine – we believe Brutus when he says it was hard for him to murder Caesar. But does his sense of patriotism really justify killing a friend and a major political leader? It turns out that this is one of the most important questions in the play, and there aren't any easy answers.

Great-Grandfather of Macbeth and Hamlet

When we first meet Brutus, it becomes clear that he's the play's most psychologically complex character. Check out his response when Cassius asks him what's bothering him:

Cassius,

Be not deceived. If I have veiled my look,

I turn the trouble of my countenance

Merely upon myself. Vexèd I am

Of late with passions of some difference,

Conceptions only proper to myself,

Which give some soil, perhaps, to my behaviors.

But let not therefore my good friends be grieved

(Among which number, Cassius, be you one)

Nor construe any further my neglect,

Than that poor Brutus, with himself at war,

Forgets the shows of love to other men. (1.2.42-53)

When Brutus says he's been at "war" with himself, we know he's pretty torn up about something. Is he worried about Caesar's growing power and what he'll probably have to do to stop him from becoming king? Probably. The rest of play traces Brutus' inner turmoil, which is why a lot of literary critics see Brutus as the great-grandfather of two of Shakespeare's later protagonists: Hamlet (the moodiest teenager in literature) and the introspective Macbeth. This speech also says a lot about Brutus' character. When Cassius asks him why he's been so upset lately, Brutus' first priority is to apologize to his pal for being so moody and neglectful of their relationship. Obviously friendship is very important to Brutus.

The Noblest Roman of Them All?

There's a reason Antony calls Brutus the "noblest Roman" (meaning most honorable): he stands up for what he believes in, risks his life for Rome, and doesn't seem to be concerned with personal gain. Yet for all of Brutus' good qualities, his troubles stem from his decision to murder a man and his misjudgment about the consequences. Brutus' defining traits are still up for discussion: is he more naïve than noble, more callous than considerate? Brutus' honor convinces him that they shouldn't dispose of Antony when the other men want to, and his trust in Antony's honor leads him to believe Antony's funeral speech will not be an invitation to riot. (Sadly mistaken.)

His final words are most telling – he doesn't die just to avenge Caesar, but instead leaves a complicated legacy: "Caesar, now be still: I kill'd not thee with half so good a will." This incantation acknowledges the debt Brutus owes to Caesar, and it admits that Brutus sees some of his own failings too – leading him to embrace his own death. It's not that Brutus didn't willingly kill Caesar. He's as committed to his own death now as he was to Caesar's then. Brutus commits an act of self-sacrifice with no pride or self-pity. He's humble about what he's done (both good and bad) and quietly accepting of his own fate.

Biggest Backstabber Ever or Roman Hero?

Brutus' decision to stab Caesar in the back isn't an easy one. He has to choose between his loyalty to the Roman Republic and his loyalty to his friend, who seems like he could be heading toward tyrant status. When Brutus hears how the commoners are treating Caesar like a rock star, he's worried for Rome:

BRUTUS

What means this shouting? I do fear the people

Choose Caesar for their king.

CASSIUS

Ay, do you fear it?

Then must I think you would not have it so.

BRUTUS

I would not, Cassius, yet I love him well. (1.2.75-89)

Even though Brutus "love[s]" Caesar "well," he also fears that his friend will be crowned king, which goes against the ideals of the Roman Republic.

After killing his pal and washing his hands in his blood, Brutus defends his actions:

If there be any in this assembly, any dear

friend of Caesar's, to him I say that Brutus' love

to Caesar was no less than his. If then that friend

demand why Brutus rose against Caesar, this is my

answer: not that I loved Caesar less, but that I loved

Rome more. (3.2.19-24)

OK, fine – we believe Brutus when he says it was hard for him to murder Caesar. But does his sense of patriotism really justify killing a friend and a major political leader? It turns out that this is one of the most important questions in the play, and there aren't any easy answers.

Great-Grandfather of Macbeth and Hamlet

When we first meet Brutus, it becomes clear that he's the play's most psychologically complex character. Check out his response when Cassius asks him what's bothering him:

Cassius,

Be not deceived. If I have veiled my look,

I turn the trouble of my countenance

Merely upon myself. Vexèd I am

Of late with passions of some difference,

Conceptions only proper to myself,

Which give some soil, perhaps, to my behaviors.

But let not therefore my good friends be grieved

(Among which number, Cassius, be you one)

Nor construe any further my neglect,

Than that poor Brutus, with himself at war,

Forgets the shows of love to other men. (1.2.42-53)

When Brutus says he's been at "war" with himself, we know he's pretty torn up about something. Is he worried about Caesar's growing power and what he'll probably have to do to stop him from becoming king? Probably. The rest of play traces Brutus' inner turmoil, which is why a lot of literary critics see Brutus as the great-grandfather of two of Shakespeare's later protagonists: Hamlet (the moodiest teenager in literature) and the introspective Macbeth. This speech also says a lot about Brutus' character. When Cassius asks him why he's been so upset lately, Brutus' first priority is to apologize to his pal for being so moody and neglectful of their relationship. Obviously friendship is very important to Brutus.

The Noblest Roman of Them All?

There's a reason Antony calls Brutus the "noblest Roman" (meaning most honorable): he stands up for what he believes in, risks his life for Rome, and doesn't seem to be concerned with personal gain. Yet for all of Brutus' good qualities, his troubles stem from his decision to murder a man and his misjudgment about the consequences. Brutus' defining traits are still up for discussion: is he more naïve than noble, more callous than considerate? Brutus' honor convinces him that they shouldn't dispose of Antony when the other men want to, and his trust in Antony's honor leads him to believe Antony's funeral speech will not be an invitation to riot. (Sadly mistaken.)

His final words are most telling – he doesn't die just to avenge Caesar, but instead leaves a complicated legacy: "Caesar, now be still: I kill'd not thee with half so good a will." This incantation acknowledges the debt Brutus owes to Caesar, and it admits that Brutus sees some of his own failings too – leading him to embrace his own death. It's not that Brutus didn't willingly kill Caesar. He's as committed to his own death now as he was to Caesar's then. Brutus commits an act of self-sacrifice with no pride or self-pity. He's humble about what he's done (both good and bad) and quietly accepting of his own fate.

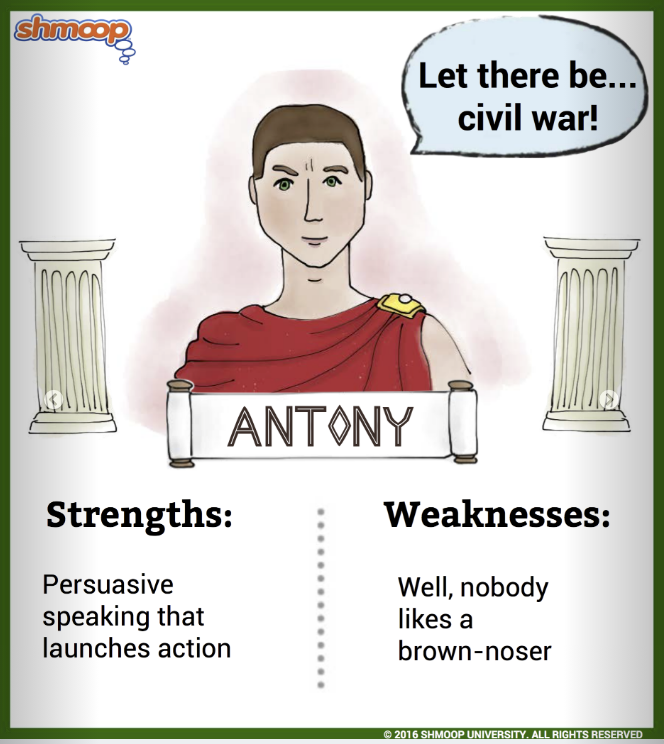

Antony

Antony is a good friend of Julius Caesar who launches himself into a major position of power over the course of the play. And, yes, this is the same Mark Antony who has a torrid love affair with Cleopatra and goes down in another Shakespeare play, Antony and Cleopatra.

Antony the Brown-Noser

When we first meet him, Antony is running around in a goatskin loincloth at the Feast of the Lupercal, agreeing to everything Caesar has to say (1.2). After being ordered to touch Calphurnia with the magic fertility whip (head over to "Symbolism" for more on this), Antony declares "When Caesar says 'do this,' it is perform'd."(1.2). By asserting that Julius Caesar's words are authoritative enough to make anything happen, Antony draws our attention to the sheer power of language in the play.

Antony the Master of Rhetoric

Antony's strong suit is rhetoric (the art of speaking persuasively), which makes him a terrific politician. After Caesar's death, Antony manages to convince the conspirators that he should be allowed to speak at Caesar's funeral. In the famous speech that begins, "Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears" (3.2.82), Antony delivers a carefully crafted eulogy that's designed to turn the people against the conspirators and launch him into a position of power. The success of Antony's speech suggests that effective leadership goes hand in hand with rhetoric because, after Antony finishes talking, all hell breaks loose and civil war ensues, which is exactly what Antony intended.

Antony the Brown-Noser

When we first meet him, Antony is running around in a goatskin loincloth at the Feast of the Lupercal, agreeing to everything Caesar has to say (1.2). After being ordered to touch Calphurnia with the magic fertility whip (head over to "Symbolism" for more on this), Antony declares "When Caesar says 'do this,' it is perform'd."(1.2). By asserting that Julius Caesar's words are authoritative enough to make anything happen, Antony draws our attention to the sheer power of language in the play.

Antony the Master of Rhetoric

Antony's strong suit is rhetoric (the art of speaking persuasively), which makes him a terrific politician. After Caesar's death, Antony manages to convince the conspirators that he should be allowed to speak at Caesar's funeral. In the famous speech that begins, "Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears" (3.2.82), Antony delivers a carefully crafted eulogy that's designed to turn the people against the conspirators and launch him into a position of power. The success of Antony's speech suggests that effective leadership goes hand in hand with rhetoric because, after Antony finishes talking, all hell breaks loose and civil war ensues, which is exactly what Antony intended.

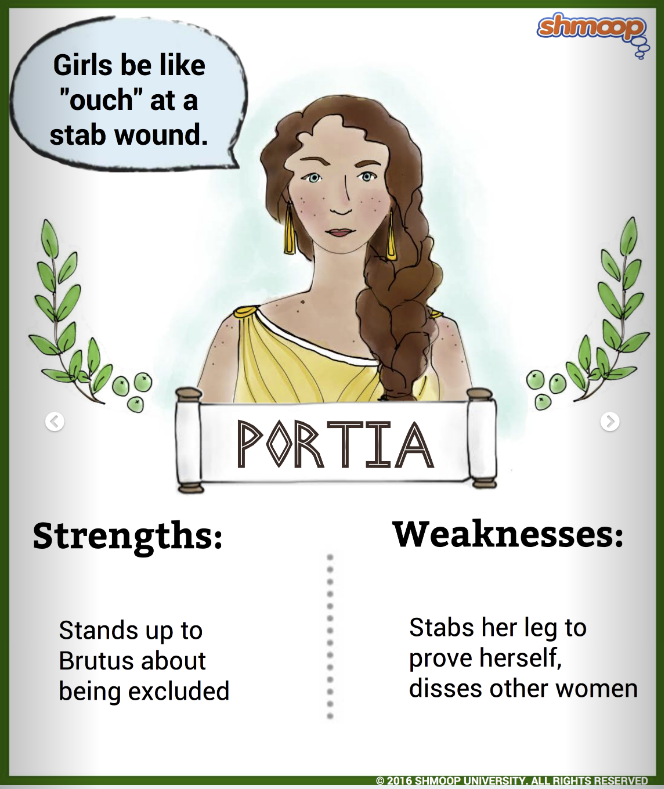

Portia

Portia is Brutus' devoted wife. She doesn't get a whole lot of stage time but we think she's an interesting figure, especially when it comes to the play's concern with gender dynamics.

When Brutus refuses to confide in Portia, she takes issue with his secrecy: as a married couple, she says, they should have no secrets.

Dear my lord,

Make me acquainted with your cause of grief.

[...]

Within the bond of marriage, tell me, Brutus,

Is it excepted I should know no secrets

That appertain to you? Am I your self

But, as it were, in sort or limitation,

To keep with you at meals, comfort your bed,

And talk to you sometimes? Dwell I but in the

suburbs

Of your good pleasure? If it be no more,

Portia is Brutus' harlot, not his wife. (2.1.275-276; 302-310)

In other words, Portia is sick and tired of being excluded from her husband's world just because she's a woman. She also suggests that, when Brutus keeps things from her, he's treating her like a "harlot [prostitute], not his wife."

Portia's desire to be close to her husband seems reasonable enough. But Portia also has the annoying habit of talking about women (including herself) as though they're weaker than men.

I grant I am a woman; but withal

A woman well-reputed, Cato's daughter.

Think you I am no stronger than my sex,

Being so fathered and so husbanded?

Tell me your counsels; I will not disclose 'em.

I have made strong proof of my constancy,

Giving myself a voluntary wound

Here, in the thigh. Can I bear that with patience.

And not my husband's secrets? (2.1.317-325)

Here Portia says she knows she's just a girl, but since she's the daughter and wife of two really awesome men, that makes her better than the average woman. To prove her point, she stabs herself in the thigh without flinching and demands that her husband treat her with more respect. Yikes! Later she kills herself by swallowing "fire," or hot coals (4.3). This is interesting because it's usually men who are prone to violence in the play.

When Brutus refuses to confide in Portia, she takes issue with his secrecy: as a married couple, she says, they should have no secrets.

Dear my lord,

Make me acquainted with your cause of grief.

[...]

Within the bond of marriage, tell me, Brutus,

Is it excepted I should know no secrets

That appertain to you? Am I your self

But, as it were, in sort or limitation,

To keep with you at meals, comfort your bed,

And talk to you sometimes? Dwell I but in the

suburbs

Of your good pleasure? If it be no more,

Portia is Brutus' harlot, not his wife. (2.1.275-276; 302-310)

In other words, Portia is sick and tired of being excluded from her husband's world just because she's a woman. She also suggests that, when Brutus keeps things from her, he's treating her like a "harlot [prostitute], not his wife."

Portia's desire to be close to her husband seems reasonable enough. But Portia also has the annoying habit of talking about women (including herself) as though they're weaker than men.

I grant I am a woman; but withal

A woman well-reputed, Cato's daughter.

Think you I am no stronger than my sex,

Being so fathered and so husbanded?

Tell me your counsels; I will not disclose 'em.

I have made strong proof of my constancy,

Giving myself a voluntary wound

Here, in the thigh. Can I bear that with patience.

And not my husband's secrets? (2.1.317-325)

Here Portia says she knows she's just a girl, but since she's the daughter and wife of two really awesome men, that makes her better than the average woman. To prove her point, she stabs herself in the thigh without flinching and demands that her husband treat her with more respect. Yikes! Later she kills herself by swallowing "fire," or hot coals (4.3). This is interesting because it's usually men who are prone to violence in the play.

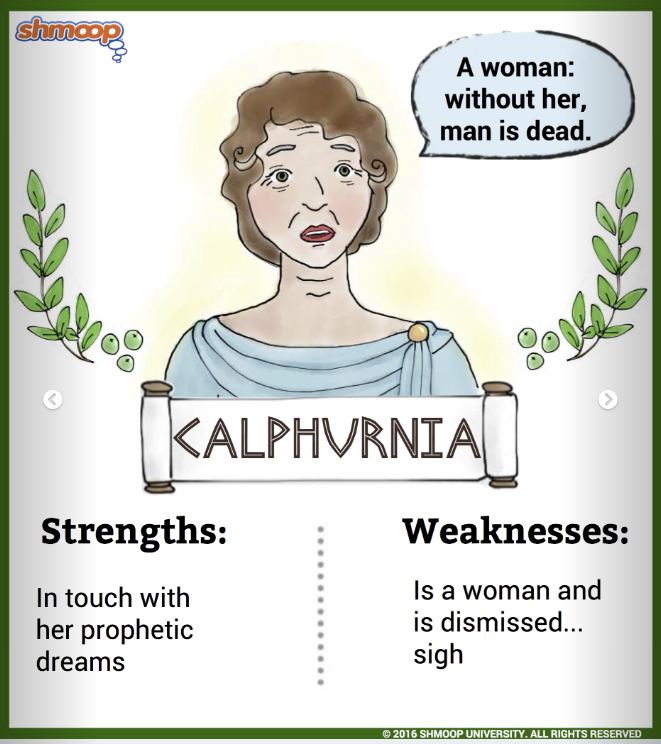

Calphurnia

Calphurnia is Julius Caesar's wife. Just before Caesar is assassinated at the Capitol, Calphurnia has an ominous dream that seems to predict Caesar's violent death. She begs Caesar to stay home, but her husband blows her off:

Calphurnia here, my wife, stays me at home.

She dreamt tonight she saw my statua [statue],

Which, like a fountain with an hundred spouts,

Did run pure blood: and many lusty Romans

Came smiling and did bathe their hands in it.

And these does she apply for warnings and portents,

And evils imminent, and on her knee

Hath begged that I will stay at home today. (2.2.80-87)

Calphurnia's dream of Caesar's body spurting blood like a fountain turns out to be pretty prophetic. (Remember, Caesar is stabbed 33 times and the conspirators stand around afterward and wash their hands in his blood.) So why doesn't Caesar pay attention to his wife? At first it seems like Caesar is going to heed his wife's warning. But Calphurnia's attempts to protect her husband are completely undermined when Decius shows up and says girls don't know how to interpret dreams. If this dream had come from someone other than Calphurnia (who is a woman and thus considered less insightful during Caesar's day), would Caesar have listened?

Calphurnia here, my wife, stays me at home.

She dreamt tonight she saw my statua [statue],

Which, like a fountain with an hundred spouts,

Did run pure blood: and many lusty Romans

Came smiling and did bathe their hands in it.

And these does she apply for warnings and portents,

And evils imminent, and on her knee

Hath begged that I will stay at home today. (2.2.80-87)

Calphurnia's dream of Caesar's body spurting blood like a fountain turns out to be pretty prophetic. (Remember, Caesar is stabbed 33 times and the conspirators stand around afterward and wash their hands in his blood.) So why doesn't Caesar pay attention to his wife? At first it seems like Caesar is going to heed his wife's warning. But Calphurnia's attempts to protect her husband are completely undermined when Decius shows up and says girls don't know how to interpret dreams. If this dream had come from someone other than Calphurnia (who is a woman and thus considered less insightful during Caesar's day), would Caesar have listened?

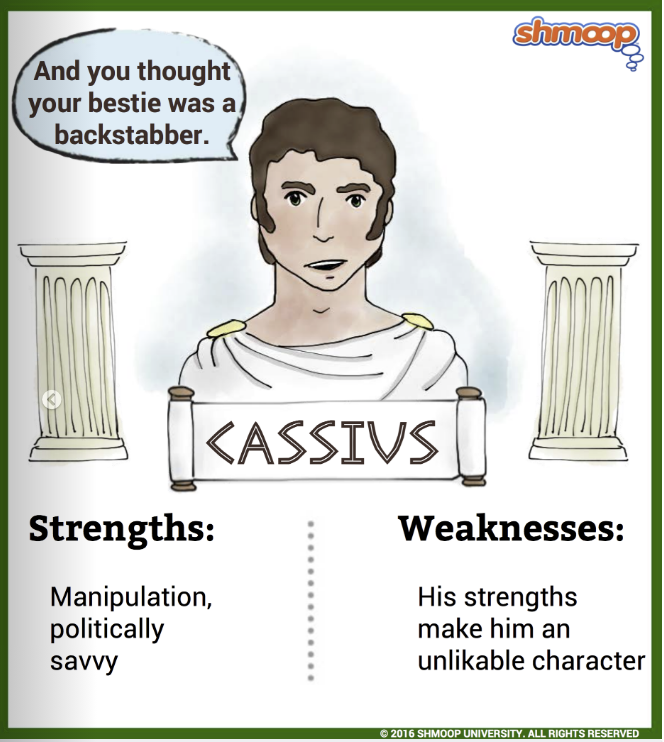

Cassius

Cassius is the ringleader of the conspirators. He's politically savvy and manipulative, and he absolutely resents the way the Roman people treat Julius Caesar like a rock star. More important, he hates the way Caesar runs around acting like a god: "Why, man, he doth bestride the narrow world /Like a Colossus, and we petty men / Walk under his huge legs and peep about" (1.2.142-144).

Cassius is also responsible for manipulating Brutus into joining the conspiracy (although Brutus may have already been thinking of turning against Caesar):

Well, Brutus, thou art noble. Yet I see

Thy honorable metal may be wrought

From that it is disposed. Therefore it is meet

That noble minds keep ever with their likes;

For who so firm that cannot be seduced? (1.2.305-309)

Bragging to the audience, Cassius compares himself to a metal-worker as he suggests that even the noblest of men can be manipulated, or bent, to his will. How does Cassius "seduce" Brutus? First he slyly suggests that the Roman people want Brutus to lead them, then he sends Brutus some forged letters urging him to take down Caesar.

Cassius is also responsible for manipulating Brutus into joining the conspiracy (although Brutus may have already been thinking of turning against Caesar):

Well, Brutus, thou art noble. Yet I see

Thy honorable metal may be wrought

From that it is disposed. Therefore it is meet

That noble minds keep ever with their likes;

For who so firm that cannot be seduced? (1.2.305-309)

Bragging to the audience, Cassius compares himself to a metal-worker as he suggests that even the noblest of men can be manipulated, or bent, to his will. How does Cassius "seduce" Brutus? First he slyly suggests that the Roman people want Brutus to lead them, then he sends Brutus some forged letters urging him to take down Caesar.

Casca

Casca is a Roman conspirator who takes part in Caesar's assassination.

Like all the other conspirators, Casca is worried that Caesar will be crowned king, which goes against the ideals of the Roman Republic. Casca is also not a big fan of Caesar's theatrics. Check out the way Casca describes how Caesar refused the crown three times and then fainted dramatically before the adoring crowd:

And then [Antony] offered it the third time. He put it the

third time by, and still as he refused it the rabblement

hooted and clapped their chapped hands and

threw up their sweaty nightcaps and uttered such a

deal of stinking breath because Caesar refused the

crown that it had almost choked Caesar, for he

swooned and fell down at it. And for mine own part,

I durst not laugh, for fear of opening my lips and

receiving the bad air. (1.2.253-261)

Casca knows that Caesar's dramatic refusal of the crown and fainting spell are just cheap tricks to curry favor with the "hoot[ing]" and "clap[ing]" crowd. What's interesting is that Casca describes the crowd as though it were a theater audience watching a performance.

Like all the other conspirators, Casca is worried that Caesar will be crowned king, which goes against the ideals of the Roman Republic. Casca is also not a big fan of Caesar's theatrics. Check out the way Casca describes how Caesar refused the crown three times and then fainted dramatically before the adoring crowd:

And then [Antony] offered it the third time. He put it the

third time by, and still as he refused it the rabblement

hooted and clapped their chapped hands and

threw up their sweaty nightcaps and uttered such a

deal of stinking breath because Caesar refused the

crown that it had almost choked Caesar, for he

swooned and fell down at it. And for mine own part,

I durst not laugh, for fear of opening my lips and

receiving the bad air. (1.2.253-261)

Casca knows that Caesar's dramatic refusal of the crown and fainting spell are just cheap tricks to curry favor with the "hoot[ing]" and "clap[ing]" crowd. What's interesting is that Casca describes the crowd as though it were a theater audience watching a performance.

Octavius

Octavius (a.k.a. "Young Octavius") is Julius Caesar's adopted son. Like his adoptive father, Octavius doesn't appear on stage that much. Throughout most of the play, Octavius is off travelling the world. He returns to Rome when Caesar is assassinated and joins forces with Antony against the conspirators.

Octavius may be "young" (Antony likes to remind him that he is older and more experienced), but he's not a pushover. Check out what happens when Antony tries to take command during the battle at Philippi.

ANTONY

Octavius, lead your battle softly on

Upon the left hand of the even field.

OCTAVIUS

Upon the right hand, I; keep thou the left.

ANTONY

Why do you cross me in this exigent? (5.1.17-20)

This minor game of tug-of-war between Octavius and Antony foreshadows what will happen between the two men after they defeat the conspirators. Although not portrayed in this play, Antony and Octavius (along with Lepidus) will go on to rule Rome as part of the "Second Triumvirate" (the first included Caesar and Pompey)

Octavius may be "young" (Antony likes to remind him that he is older and more experienced), but he's not a pushover. Check out what happens when Antony tries to take command during the battle at Philippi.

ANTONY

Octavius, lead your battle softly on

Upon the left hand of the even field.

OCTAVIUS

Upon the right hand, I; keep thou the left.

ANTONY

Why do you cross me in this exigent? (5.1.17-20)

This minor game of tug-of-war between Octavius and Antony foreshadows what will happen between the two men after they defeat the conspirators. Although not portrayed in this play, Antony and Octavius (along with Lepidus) will go on to rule Rome as part of the "Second Triumvirate" (the first included Caesar and Pompey)

Soothsayer

This is the guy who famously and cryptically warns Caesar to "beware the Ides of March" (1.2.21). The "Ides of March" refers to March 15, the day Julius Caesar is assassinated by the Roman conspirators. Even though he gets to speak the coolest line in the play, nobody pays any attention to the soothsayer (except the audience, who knows all about how the historical Julius Caesar was stabbed in the back that day).

The soothsayer's warning raises an interesting question about fate and free will. If Caesar had actually heeded the warning to "beware the Ides of March," could he have changed the course of events that day? On the one hand, the soothsayer's warning about his impending doom (along with all the other creepy omens in the play) suggests that Caesar's fate is already decided. On the other hand, why would the soothsayer bother warning Caesar if there was nothing he could do to prevent his death? For more on this, see "Themes: Fate and Free Will."

The soothsayer's warning raises an interesting question about fate and free will. If Caesar had actually heeded the warning to "beware the Ides of March," could he have changed the course of events that day? On the one hand, the soothsayer's warning about his impending doom (along with all the other creepy omens in the play) suggests that Caesar's fate is already decided. On the other hand, why would the soothsayer bother warning Caesar if there was nothing he could do to prevent his death? For more on this, see "Themes: Fate and Free Will."

Cinna (the Conspirator)

We first meet Cinna in Act 1, Scene 3, where he schemes with Cassius about how to get Brutus to join the conspiracy against Caesar. He's also assigned the task of planting some phony documents in Brutus' room. Cinna the conspirator shouldn't be confused with Cinna the poet.

Cinna (the Poet)

This poor guy is the victim of mistaken identity when an angry mob confronts him on the streets of Rome:

CINNA THE POET

Truly, my name is Cinna.

FIRST PLEBIAN

Tear him to pieces! He's a conspirator.

CINNA THE POET

I am Cinna the poet, I am Cinna the poet!

FOURTH PLEBIAN

Tear him for his bad verses, tear him for his bad verses!

CINNA THE POET

I am not Cinna the conspirator.

FOURTH PLEBIAN

It is no matter. His name's Cinna.

Pluck but his name out of his heart, and turn him

going. (3.3.28-36)

Yikes! Even after he declares his true identity to the angry mob, he's ripped to shreds for his "bad verses." Cinna's violent death seems emblematic of the disorder that ensues after Caesar's assassination. With Caesar dead, Rome falls into utter chaos and nobody is safe.

CINNA THE POET

Truly, my name is Cinna.

FIRST PLEBIAN

Tear him to pieces! He's a conspirator.

CINNA THE POET

I am Cinna the poet, I am Cinna the poet!

FOURTH PLEBIAN

Tear him for his bad verses, tear him for his bad verses!

CINNA THE POET

I am not Cinna the conspirator.

FOURTH PLEBIAN

It is no matter. His name's Cinna.

Pluck but his name out of his heart, and turn him

going. (3.3.28-36)

Yikes! Even after he declares his true identity to the angry mob, he's ripped to shreds for his "bad verses." Cinna's violent death seems emblematic of the disorder that ensues after Caesar's assassination. With Caesar dead, Rome falls into utter chaos and nobody is safe.

Flavius and Murellus

Flavius and Murellus are two snooty conspirators against Caesar. In the opening scene, they catch a bunch of commoners celebrating Caesar's victorious return to Rome and try to give them a spanking for not being hard at work. Check out what Flavius says (and pay attention, because these are the very first lines spoken in the play):

Hence! home, you idle creatures, get you home!

Is this a holiday? What! know you not,

Being mechanical, you ought not walk

Upon a laboring day without the sign

Of your profession?—Speak, what trade art thou? (1.1.1-5)

Hence! home, you idle creatures, get you home!

Is this a holiday? What! know you not,

Being mechanical, you ought not walk

Upon a laboring day without the sign

Of your profession?—Speak, what trade art thou? (1.1.1-5)